It's not often I get a repair or GammelGura back. But I got this renovation back when it turned out that the guitar played false above the 12th fret. In a GammelGura I always double-check the fret placement if an original fretboard is to be reused, this was a renovation.

All frets below 12th were placed by eye, no less than 4 mm error in the placement on the worst frets! It's a phenomenon I've come across several times on 1800th century guitars, that the frets up to the 12th are OK, while the ones below are completely misplaced. What this is due to can be speculated on, perhaps there was a table that many people used that ended at the 12th fret. Whatever the reason, it doesn't cost more to place the frets correctly instead of incorrectly. You might think it's a bit charming and that the correct placement looks more boring and less organic, but if you're playing the guitar, it's probably best that they're in the right place.

To move the frets, the old fret slots must be filled again with sticks in the same type of wood as the fingerboard. The frets were of the type "bar frets", they are completely flat and as thick as the top of the T in modern T-bands. They also have the function of giving the neck a backward bend by pressing down thicker frets than the frett slot is wide. With different thick bar frets, you can adjust the back bend and keep the neck straight with taut strings. It is an art that few have mastered these days. Only Martin kept bar frets right up until the 1930s, if you see bar frets on an old guitar it is most likely a guitar from the 1800th century. In parentheses, the modern T-fret on the Bay State guitar dated to about 1888 was in the current batch, and they appear to be original, they probably came earlier than I thought.

There was a risk that the neck would be bent more by the string pull when changing to regular T-frets. But since the fingerboard was very thin and in rosewood, which is not the hardest wood, I didn't think it would be a problem. It was later found that the relief became larger with the T-frets.

It was relatively easy to pull up the bar frets with pliers. If they had been completely smooth there would have been no problem at all, but many notches had been made with a knife on the underside of the brass frets with small sharp protruding bristles as a result to make them more secure. The small chips in the fretboard that were pulled up with the frets were quickly glued back with thin superglue before they would come off. Modern T-frets have "nibs" to make them more secure, there you always have problems with the fingerboard wanting to split when the frets are pulled up.

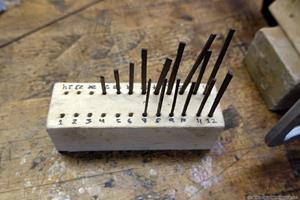

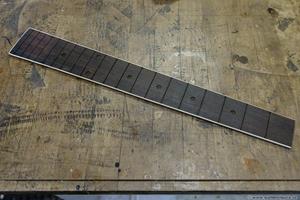

Sticks in rosewood with the same thickness as the fret slots were wide were made and cut to the right length and height.

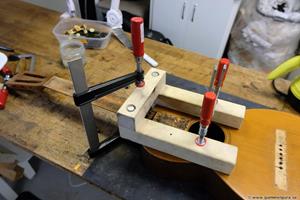

The extreme radius of the fretboard was bigger than the 6″, which is the most curved insert you can buy for my fret press. I had to custom make an insert with a larger bend and also a stop to hold down the most recently installed fret while the glue dried. Even the tool for bending the new frets had to be converted with an extra screwdriver to be able to make the big bend!

The straight sticks were glued with superglue and pressed into place. When the glue dried, the excess was planed down and the sticks were sanded against the board.

By measuring the distance to the 12th fret, which I used to intonate the bridge, and multiplying by two, I got the open string length (scale) 607mm. About 10 years ago I used Stewmac's fret calculator and printed out a stack of A4 sheets with the distances for all the frets for most guitar and mandolin gauges at 1mm intervals on open string length. The sheets are collected in a folder, and it is quick and easy to find the right measurements. The fret locations were measured on the fretboard with my 50 cm long caliper with 0.1 mm precision and marked with a sharp awl. All the frets up to the 12th were placed about 1 mm too far up the fretboard, the ones below 3-4 mm wrong except for the very last fret which was actually in the right place.

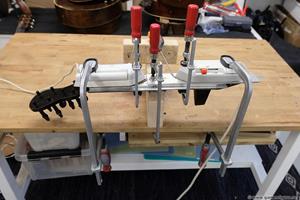

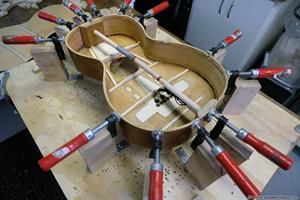

Usually the fretboard is loose, and I can use my Stewmac saw box jig to cut the frets parallel and to the correct depth. When the board is attached to a guitar, I instead make a temporary jig from a straight wooden beam, some wooden clamps, pliers and an angle. Using my cool center finder, it's easy to draw a center line along the tapered fretboard. The neck is clamped so that the distance between the wooden beam and the center line is the same at both ends. The angle is placed so that the saw cut ends up in the middle of the mark. The saw is guided by the edge to the angle, and I saw a fret notch no deeper than the fret tang.

Once all the slots are cut, I use a fret saw with a stop to cut the fret slots to the same depth, just a little deeper than the fret tang. To protect the surface of the fingerboard from abrasion from the saw stop, I use a thin aluminum plate between the saw stop and the fingerboard. Finally, the edge to the notch is chamfered off with a square needle file. I have bought a set of needle files with a coarser cut than the fine one you usually see in hardware stores. I also have a set of needle files in the form of rasps, the round rasp is perfect for filing up the notches for the strings in the bridge for unslotted string pegs.

The fretting was tricky as the fingerboard had such a large radius, but with the specially made insert for the fret press it worked fine. The frets were glued with superglue. Nowadays, I mount every other fret (all odd and then all even frets) to reduce the backward bend from the tang in the fret slots, but in this case I should have fretted as usual! It turned out that the relief was a full 0,7 mm in the middle with tensioned strings, my ideal is about 0,15 mm.

I don't really know why, but the compression and back bend from the bar frets is certainly greater than the one you get from the T-fret tangs. The neck also had a little too much relief even before I refretted. Next time I do something similar, I'll brace the neck to a slight back bend and open up the fret slots a bit more before fitting and gluing the wooden sticks.

So, what do you do? You don't want to play a banana neck. My patented solution, which is the very best, is to mill in a carbon fiber rod under the fretboard. But in this case it would have been a lot of extra work and besides, the fingerboard was so thin and bent that it probably couldn't have been saved. In addition, the frets would have to be reattached once more. There are two solutions, to heat-bend the neck straight or replace the frets with frets with a thicker tang. I chose to start with heating and only change frets in case of emergency.

Bending back the neck with heat is a double-edged sword, you can succeed, but it's always a gamble. A disadvantage is that the heat always dries out the fingerboard so that it shrinks and that the lacquer under the neck at the stop can melt from the heat and be damaged. To reduce the shrinkage of the fingerboard, one should first saturate the fingerboard with oil. What you are looking for is to heat the fretboard and the neck wood hotter than the melting point of the lignin and at the same time bend the neck back to a curve roughly the same size as the banana bend/relief, but in the other direction. Wood consists of equal parts cellulose fibers, lignin and hemicellulose, lignin is a bit like a putty that binds the cellulose fibers together. It is hoped that the lignin will solidify into its new form as it cools and that the neck will become more or less straight with the strings at tension.

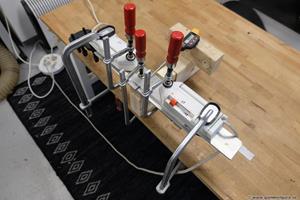

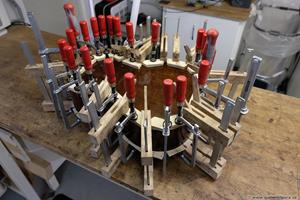

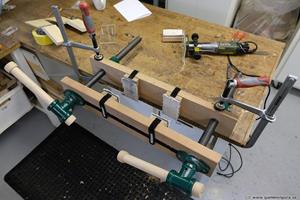

My jig consists of an aluminum plate that is thick enough to give the back bend an even curvature and at the same time distribute the heat evenly. In this case, the fingerboard was longer than both of my two plates, so I had to use both and a shim to cover the entire fingerboard. The neck gets a rest just at the spot where the relief bend of the fingerboard is deepest. It is important that the surface of the stop is smooth and even, otherwise you can get a pattern pressed into the soft lacquer if the lacquer becomes sticky from the heat. A little household plastic between the stop and the neck means that the lacquer cannot stick to the stop. The clamps are tightened so tightly at both ends that the fretboard/neck gets a backward bend that is as big, or a little bigger, than the relief was before. You aim along the edge of the fretboard and hope for the best. A practical digital temperature gauge allows you to easily adjust the temperature of the irons, which are regulated with a thermostat.

The large radius of the fingerboard was a problem as I couldn't get good contact between the fretboard and the frets to transfer the heat, but I solved that by sandwiching thin strips of metal on the sides between the frets and the fretboard.

After thinking about this in retrospect, perhaps I happened to do things more right than I thought. The greatest bending of the neck always occurs near the nut, where the breaking of the strings over the nut gives an extra bending force. With two overlapping aluminum plates at the bottom end of the fretboard, the bending from the clamps was greatest on the upper part of the neck in my jig, where I only had one aluminum plate. The lower part with double aluminum plates was stiffer and bent less. It also occurred to me that you can use a layer of folded aluminum foil shaped according to the fingerboard radius to fill in between the aluminum plate and the fingerboard to more effectively conduct the heat down into the neck. I also have to mention that it takes a lot of force on the clamps to bend back a guitar neck, perhaps in the region of 20-50 kg of pressure on the middle caul under the neck. I use a caul that is shaped to the neck and lined with soft rubber.

The melting point of lignin should be about 65 degrees C. I made a first attempt with about 70 degrees C measured on the iron. Absolutely nothing happened, the same banana bend as before. I repeated the process with 5 hours of heating and a few hours of cooling before loosening the clamps with 100 degrees C on the irons. With 100 degrees C in the irons and aluminum plates, the temperature on the back of the neck was 42 degrees C. This means that the lignin in the fretboard and the neck closest to the fretboard will be reshaped, but not in the entire neck. I think you should reach at least 80 degrees C to successfully soften the lignin.

The result was successful, an essentially completely straight neck and a minimal shrinkage of the fingerboard. I just had to trim down the frets ends that stuck out a little. The lacquer had also done well under the counter-hold. Time to send the guitar back again, hopefully it doesn't play out-of-tune anymore!